ANSWER: Regardless of whether the lawyer is representing a civil client or a criminal client, the lawyer’s ethical obligations remain the same. Where a client informs counsel of his intent to commit perjury, a lawyer’s first duty is to attempt to dissuade the client from committing perjury.

Full Answer

What are a lawyer's ethical obligations to a criminal client?

However, Rule 3.3 (c), Ala. R. Prof. C., does allow a lawyer to refuse to offer evidence on behalf of a client that the lawyer reasonably believes to be false. While the Comment to Rule 3.3 also addresses the ethical obligations of lawyers in their representation of criminal clients, the outcome is less clear.

Can a client tell a lawyer the location of evidence?

Apr 01, 2021 · But according to professor Peter A. Joy of Washington University School of Law, there are other ethics rules that come into play when a pleading is unsupported by evidence, including Rules 4.1, 5 ...

Are lawyers obliged to preserve attorney-client confidentiality?

Since Rule 3.6(l)(1) prohibits disclosures except where “required by law,” and since § 455 and 753 specifically prohibit concealment of physical evidence without apparent regard for whether such evidence is held by an attorney by virtue of the attorney‑client relationship, it can be argued that the obligation of § 455 and 753 clearly controls and mandates disclosure by the Attorney.

Can a client refuse to reveal false evidence to a lawyer?

Dec 29, 2005 · The dilemma arises when a lawyer obtains physical evidence such as a gun that relates to a crime for which a client faces possible charges. A lawyer in that situation must find a way to resolve ...

Does attorney-client privilege apply to physical evidence?

The attorney-client privilege only protects physical evidence if that evidence, for example, a letter, was created in the course of a confidential communication made for the purpose of seeking legal advice.

What are the legal and ethical responsibilities of the defense attorney who represent clients in criminal cases?

The defense lawyer's duty to represent the defendant's interests is balanced by his duty to act in an ethical and professional manner. ... The defense lawyer has a duty to disclose any relevant laws or rulings to the court that are directly adverse to the defendant and that have not been disclosed by the prosecutor.Sep 26, 2012

Do clients tell their lawyers if they are guilty?

In truth, the defense lawyer almost never really knows whether the defendant is guilty of a charged crime. Just because the defendant says he did it doesn't make it so. ... For these reasons, among others, defense lawyers often do not ask their clients if they committed the crime.

Is attorney-client privilege an ethical rule?

It applies in all Page 2 situations, though a lawyer may be required to testify regarding client communications under compulsion of law. So, if a court determines that particular information is not covered by the attorney-client privilege, it still may be covered by the lawyer's ethical duty of confidentiality.

What are the ethical obligations of a prosecutor and a defense attorney?

Prosecutorial EthicsRefrain from prosecuting a charge that the prosecutor knows is not supported by probable cause;Make reasonable efforts to assure that the accused has been advised of the right to, and the procedure for obtaining, counsel and has been given reasonable opportunity to obtain counsel;More items...•Aug 7, 2018

How would you deal with the ethical issues involved in being a criminal defense attorney?

0:464:44Ethical Issues for Defense Attorneys - YouTubeYouTubeStart of suggested clipEnd of suggested clipAttorneys are supposed to avoid any conflicts of interest when defending clients. The attorney mustMoreAttorneys are supposed to avoid any conflicts of interest when defending clients. The attorney must not represent two clients who are of opposing interests for instance co-defendants.

Why do lawyers ask their clients if they are guilty?

Some attorneys say that they just assume that all their clients are guilty because it helps them critically evaluate the case and decide how to present the best defense. If they allow themselves to believe that their client is innocent, they might miss out on a more compelling argument.

Can a lawyer defend someone they think is guilty?

There is a huge difference between knowing someone is guilty and suspecting or believing they're guilty. We work under extremely strict rules of ethics and we're subject to the law. It's obviously unethical and illegal for a lawyer to deceive a court knowingly.Jan 7, 2006

Can a lawyer refuse to defend a client?

Rule 2.01 - A lawyer shall not reject, except for valid reasons, the cause of the defenseless or the oppressed. Rule 2.02 - In such cases, even if the lawyer does not accept a case, he shall not refuse to render legal advice to the person concerned if only to the extent necessary to safeguard the latter's rights.

Under what circumstances can an attorney reveal information about the client that the attorney obtained during the representation of that client?

(a) A lawyer shall not reveal information relating to the representation of a client unless the client gives informed consent, the disclosure is impliedly authorized in order to carry out the representation or the disclosure is permitted by paragraph (b).

Can an attorney invoke attorney-client privilege?

While an attorney may invoke the privilege on behalf of a client, the right originates with the client. ... Communication must occur solely between the client and attorney. Communication must be made as part of securing legal opinion and not for purpose of committing a criminal act.Jul 25, 2014

What communication is protected by attorney-client privilege?

Virtually all types of communications or exchanges between a client and attorney may be covered by the attorney-client privilege, including oral communications and documentary communications like emails, letters, or even text messages. The communication must be confidential.

How many books has John C. Kennedy written?

He is the author, co-author or co-editor of more than 40 books. For much of his career, he has focused on the First Amendment and professional responsibility. Give us feedback, share a story tip or update, or report an error.

Is a frivolous case meritless?

“All frivolous cases are meritless, but not all meritless cases are frivolous,” explains Alexander Reinert of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. “My working definition is this: Frivolous cases are those that a judge can determine, at the moment of filing, to have a zero chance of success. It takes no legal argumentation or factual development to make that determination. Meritless cases are those that require some consideration—either turning over legal argumentation or considering the need for factual development—before concluding that there can be no relief of any kind for the plaintiff.”

What is unlawful obstruction in Texas?

“Unlawful” obstruction or concealment in general . Rule 3.04 (a) of the Texas Disciplinary Rules of Professional Conduct prohibits the unlawful obstruction, concealment, alteration or destruction of evidence. Rule 3.04 (a) provides:

What does "unlawfully" mean in the law?

Nevertheless, as discussed below, the term “unlawfully” is generally understood to refer to conduct that violates a statute, court order, or other mandatory disclosure obligation.

What is a statement of facts?

Statement of Facts. A lawyer represents a client who is in jail awaiting trial in a felony domestic violence case. While in jail, the defendant receives several letters from a victim in the case that contain relevant information. The defendant gives those letters to the lawyer, who takes the letters to his office for safekeeping.

Can a lawyer take possession of evidence?

A lawyer who elects to take possession of tangible evidence from a client in a criminal matter may not conceal that evidence from a prosecuti ng attorney or obstruct access to that evidence if doing so would be “unlawful.” A lawyer’s conduct with regard to potentially relevant evidence is unlawful if it is prohibited by statute, court order, or Mandatory Disclosure Obligation, as defined above. In general, however, a Texas lawyer is not required to disclose ordinary tangible evidence in a criminal matter in the absence of a court order or agreement.

What is the exception to the duty of confidentiality?

. . to prevent the client from committing a crime.” This provision is nearly identical to its counterpart in the former Code, DR 4-101(C)(3), which permitted the lawyer to reveal the “intention of a client to commit a crime and the information necessary to prevent the crime.” This exception is limited to instances in which the client’s conduct, and not someone else’s, will constitute an actual crime. In exercising her discretion under Rule 1.6(b)(2), a lawyer should consider those factors set out in Comment [6A] to Rule 1.6, as discussed in Part III of this paper.

What is confidential information?

A “confidence” referred to information protected by the attorney-client privilege, while a “secret” referred to other information “gained in the professional relationship that the client has requested be held inviolate or the disclosure of which would be embarrassing or would be likely to be detrimental to the client.” Rule 1.6 abandons the dichotomy between “confidence” and “secret” and instead defines a single concept of “confidential information.” Confidential information consists of information gained during or relating to the representation of a client, whatever its source, that is:

What is Rule 3.3(a)(3)?

Rule 3.3(a)(3) prohibits a lawyer from knowingly offering or using evidence that the lawyer knows to be false. In another of the more significant changes in the new Rules, Rule 3.3(a)(3) goes on to require that if a lawyer’s client or a witness called by the lawyer has offered material evidence and the lawyer comes to know of its falsity, the lawyer must take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal. In other words, disclosure may be required to remedy false evidence by the lawyer’s client or witness, as a last resort, even if the information to be disclosed is otherwise “protected” client confidential information.

What is a tribunal?

§ 1200.1(f). As defined in Rule 1.0(w), “tribunal denotes a court, an arbitrator in an arbitration proceeding or a legislative body, administrative agency or other body acting in an adjudicative capacity .” The definition goes on to provide that “[a] legislative body acts in an adjudicative capacity when a neutral official, after the presentation of evidence or legal argument by a party or parties, will render a legal judgment directly affecting a party’s interests in a particular matter.” Furthermore, Comment [1] to Rule 3.3 indicates that the Rule “also applies when the lawyer is representing a client in an ancillary proceeding conducted pursuant to the tribunal’s adjudicative authority, such as a deposition.” This application of Rule 3.3 to discovery proceedings has been confirmed in two ethics opinions. See ABA Formal Opinion 93-376 (1993); New York County Bar Association Opinion 741 (2010).

What happens after a lawyer terminates a client relationship?

[1] After termination of a lawyer-client relationship, the lawyer owes two duties to a former client. The lawyer may not (i) do anything that will injuriously affect the former client in any matter in which the lawyer represented the former client, or (ii) at any time use against the former client knowledge or information acquired by virtue of the previous relationship. (See Oasis West Realty, LLC v. Goldman (2011) 51 Cal.4th 811 [124 Cal.Rptr.3d 256]; Wutchumna Water Co. v. Bailey (1932) 216 Cal. 564 [15 P.2d 505].) For example, (i) a lawyer could not properly seek to rescind on behalf of a new client a contract drafted on behalf of the former client and (ii) a lawyer who has prosecuted an accused person* could not represent the accused in a subsequent civil action against the government concerning the same matter. (See also Bus. & Prof. Code, § 6131; 18 U.S.C. § 207(a).) These duties exist to preserve a client’s trust in the lawyer and to encourage the client’s candor in communications with the lawyer.

What is the rule of a lawyer?

Subject to rule 1.2.1, a lawyer shall abide by a client’s decisions concerning the objectives of representation and, as required by rule 1.4, shall reasonably* consult with the client as to the means by which they are to be pursued. Subject to Business and Professions Code section 6068, subdivision (e)(1) and rule 1.6, a lawyer may take such action on behalf of the client as is impliedly authorized to carry out the representation. A lawyer shall abide by a client’s decision whether to settle a matter. Except as otherwise provided by law in a criminal case, the lawyer shall abide by the client’s decision, after consultation with the lawyer, as to a plea to be entered, whether to waive jury trial and whether the client will testify.

What is the duty of undivided loyalty?

The duty of undivided loyalty to a current client prohibits undertaking representation directly adverse to that client without that client’s informed written consent.* Thus, absent consent, a lawyer may not act as an advocate in one matter against a person* the lawyer represents in some other matter, even when the matters are wholly unrelated. (See Flatt v. Superior Court (1994) 9 Cal.4th 275 [36 Cal.Rptr.2d 537].) A directly adverse conflict under paragraph (a) can arise in a number of ways, for example, when: (i) a lawyer accepts representation of more than one client in a matter in which the interests of the clients actually conflict; (ii) a lawyer, while representing a client, accepts in another matter the representation of a person* who, in the first matter, is directly adverse to the lawyer’s client; or (iii) a lawyer accepts representation of a person* in a matter in which an opposing party is a client of the lawyer or the lawyer’s law firm.* Similarly, direct adversity can arise when a lawyer cross-examines a non-party witness who is the lawyer’s client in another matter, if the examination is likely to harm or embarrass the witness. On the other hand, simultaneous representation in unrelated matters of clients whose interests are only economically adverse, such as representation of competing economic enterprises in unrelated litigation, does not ordinarily constitute a conflict of interest and thus may not require informed written consent* of the respective clients.

Can a lawyer represent a client without written consent?

A lawyer shall not , without informed written consent* from each client and compliance with paragraph (d), represent a client if the representation is directly adverse to another client in the same or a separate matter.

What is an other pecuniary interest?

[1] A lawyer has an “other pecuniary interest adverse to a client” within the meaning of this rule when the lawyer possesses a legal right to significantly impair or prejudice the client’s rights or interests without court action. (See Fletcher v. Davis (2004) 33 Cal.4th 61, 68 [14 Cal.Rptr.3d 58]; see also Bus. & Prof. Code, § 6175.3 [Sale of financial products to elder or dependent adult clients; Disclosure]; Fam. Code, §§ 2033-2034 [Attorney lien on community real property].)However, this rule does not apply to a charging lien given to secure payment of a contingency fee. (See Plummer v. Day/Eisenberg, LLP (2010) 184 Cal.App.4th 38 [108 Cal.Rptr.3d 455].)

Can a lawyer enter into a business transaction with a client?

lawyer shall not enter into a business transaction with a client, or knowingly* acquire an ownership, possessory, security or other pecuniary interest adverse to a client, unless each of the following requirements has been satisfied:

Can a lawyer use client information?

lawyer shall not use a client’s information protected by Business and Professions Code section 6068, subdivision (e)(1) to the disadvantage of the client unless the client gives informed consent,* except as permitted by these rules or the State Bar Act.

What is the duty of a lawyer?

Under our democratic system of governance, decisionmakers for government institutions have a duty to foster the trust of society at large in the decisions they make on behalf of their institutions. For inside—i.e., public—lawyers, this duty to foster trust constitutes an ethical responsibility requiring them, during their decision-making processes, to take into account the extralegal considerations affecting the public’s willingness to trust and accept their decisions. At a time when the majority of the American public does not trust its government, and while claims of “fake news” seek to deepen that distrust by undermining the credibility of government institutions, inside lawyers must give practical effect to this ethical responsibility.

How does a society function?

A society functions through private and government institutions. Public trust in these institutions is required in order for a democratic system of governance to succeed in governing a society.

Popular Posts:

- 1. how long does an attorney have to do discovery in yexas

- 2. why would an attorney resign bar membership

- 3. how courts calculate attorney fee awards

- 4. what you need to go to college for to be a attorney general

- 5. how to become your own divorce attorney

- 6. when your attorney doesnt try to negotiate your case

- 7. attorney who works for commission

- 8. where is trump's attorney rudy

- 9. why can't defense attorney be at presentence investigation

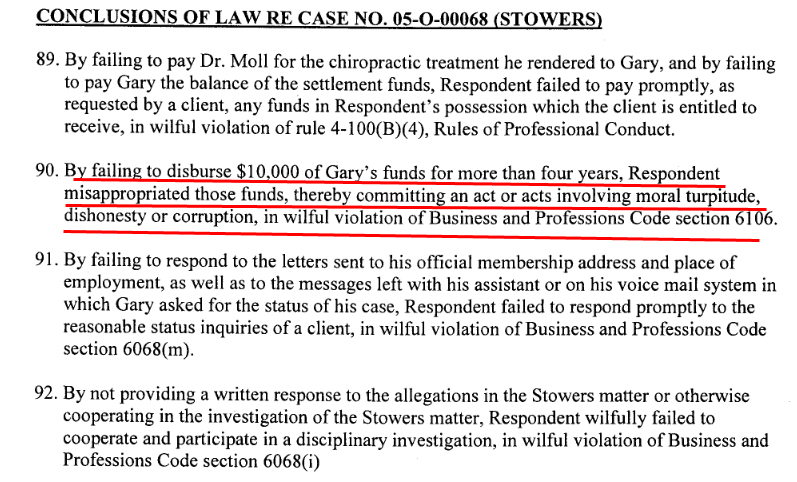

- 10. attorney involved in when they see us fired